HHH Blog

12. Happiness Ingredient: Circumstances

PUBLISHED 3rd May , 2016

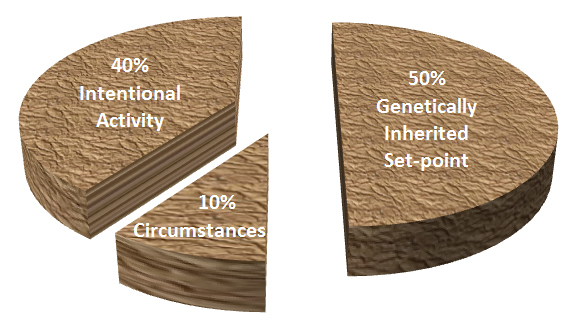

Previously I shared the finding that about half of our level of happiness is due to our genetic predisposition, also called the set-point.1 For some this might seem proof that happiness is as unachievable as ever, because they always had a tendency to melancholy or anxiousness. Or perhaps they are born pessimists like Martin Seligman and given to automatic catastrophic thoughts.2 Sonja Lyubomirsky, however, has translated scientific conclusions on the determents of happiness in a pie chart:3

This chart (which is meant to look like a chocolate cake but somehow resembles a cow pad) shows that although the set-point is the largest portion determining our level of emotional wellbeing, our intentional activities are almost as important. It highlights the fact that we can do a great deal to feel better and make our lives more satisfying. Our happiness level is certainly not set in stone.

Further, the chart is excellent for busting the persisting myth that wellbeing is the result of ideal circumstances. Indeed, our circumstances such as our gender, ethnicity, living conditions, wealth, age, level of education, whether we are beautiful or ugly, or live by the ocean or in the desert, have a miserly 10% impact on our wellbeing.4 I find this quite astonishing, perhaps because I feel that throughout, we have been taught to believe that wealth, beauty, comfort and status will bring us happiness. Nevertheless, in order to increase our psychological wellbeing, we must learn to believe in this scientific conclusion. This is best achieved by understanding it.

There is a reason why our circumstances have such minimal influence on our happiness: it is because human beings quickly get used to the way things are. According to Lyubomirsky, we have an inborn capacity to grow accustomed to most of life’s changes. Psychologists call this phenomenon hedonic adaptation. This capacity to adopt is a blessing, because it helps us to adjust to changes, setbacks and losses. However, if we seek happiness within our cultural and societal values, hedonic adaptation will present a continuous obstacle to attaining it. Not only do we tend to take nearly everything positive that happens to us for granted within a short time, we also are inclined to feel entitled to the privileges, luxuries and securities we enjoy because we are used to having them. Thus regardless of whether we move to a bigger house, buy a flashy new car, get a nose job or a land a promotion, the happiness resulting from the event will only last for a short time. At first we are thrilled, but weeks down the track the event doesn’t even register.5

Positive Psychologist Tal Ben-Shahar, who previously ran one of the most popular study courses in the history of Harvard University, writes about his experience of winning the Israeli national squash championship at age sixteen. For five years he had trained extremely hard to achieve this feat. Throughout these years he was convinced that winning would bring him happiness and alleviate the emptiness he often felt. When he did win he felt thoroughly ecstatic and blissfully happy, and went out with his family and friends to celebrate. When he got home, he sat on his bed to savour his immense feeling of happiness. However, at that precise point his happiness rush disappeared, only to be replaced with his former sense of emptiness.6

Of course working toward bettering our circumstances and achieving goals we set ourselves are ingrained human motivations and a reason for human progress. In fact, aiming to achieve personally meaningful goals is a core ingredient of psychological wellbeing.7 The nuance of whether achievement brings happiness thus lies in the reasons we pursue it. If we strive for achievements simply because they are imposed and valued by our societal and cultural environment, without having established that they are innately important to us and align with our values, we will find ourselves getting nowhere in terms of happiness.

This is because we will simply be pounding the hedonic treadmill. According to Diener, Lucas and Scollon, the hedonic treadmill theory holds that our states of happiness or unhappiness are short lived reactions to life events, after which we return to our set-points. The theory challenges the belief that happiness is around the corner of the next goal achieved, problem solved, or relationship gained, because within a short time, new goals will arise on the horizon and thus wellbeing remains unchanged.8 This is a crucial piece of happiness theory to remember because it illumines why circumstances have such small impact on wellbeing. On a treadmill one exerts a lot of effort, but one never physically gets anywhere – other than to a point of exhaustion. I think most of us, when we reflect on how this theory fits into real life; can sense how accurately it describes a fruitless chase for happiness. One that too many of us take part in.

There are qualifications within the hedonic treadmill model. Diener, Lucas and Scollon point out that adaption varies among individuals. Further, there are certain positive and negative life events that can affect wellbeing over long periods of time. For example, a divorce, losing a life partner to death, being laid off work, or becoming paralysed will likely have long-lasting impact on our wellbeing, as will marrying someone with whom one goes from strength to strength. Another qualification is that the economic environment and human rights status of a nation strongly predict the average wellbeing of citizens. Diener and colleagues suggest that conditions in life circumstances that more readily affect our wellbeing are those that keep drawing our attention.9 Thus if we want to ascertain whether a change in circumstances can have a long term affect on our wellbeing, we need to consider whether it will have ongoing impact.

A promotion can make us happier if we can use our character strengths more frequently; the extra pay we will get used to spending in a very short time. A new home in a better suburb can raise our wellbeing if it allows us to go running in a park we love; the status of living at a better address will not. Many people are victims of circumstances, sometimes rightly feeling that their problem(s) keep them from happiness. Hopefully, they will take heart from remembering the 40% of the happiness pie. We all desire a perfect life, but few of us get one. Let’s step off the hedonic treadmill of believing that ideal circumstances will make us happy. If we have a problem we cannot solve right now let us nevertheless find moments in which life is beautiful.

Today I suggest you write a list of things and people you tend to take for granted. Then sit with this list, and promise yourself to feel more appreciation for every big and small thing that is good in your life.

© Natalie Lydia Barker 2015

Notes

- Sonja Lyubomirsky, The How of Happiness: A Scientific Approach to Getting the Life You Want (New York: The Penguin Press, 2008).

- Martin Seligman, Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being (North Sydney: Random House Australia, 2011).

- Lyubomirsky, The How of Happiness.

- Lyubomirsky, The How of Happiness.

- Lyubomirsky, The How of Happiness.

- Tal Ben-Shahar, Happier: Learn the Secrets to Daily Joy and Lasting Fulfilment (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2007).

- Seligman, Flourish.

- Ed Diener, Richard E. Lucas and Christie Napa Scollon, “Beyond the Hedonic Treadmill: Revising the Adaptation Theory of Well-Being,” American Psychologist 61, no. 4 (2006).

- Diener, Lucas and Scollon, “Beyond the Hedonic Treadmill”.

No Comments